Giving to the poor is an important practice in the Anglican tradition, as is the case in most branches of Christianity. Any reading of Scripture will produce a myriad of verses regarding the importance of showing mercy and generosity towards the poor and the “least of these.” While this practice may be new for many, it is both the language and perspective through which the Anglican tradition speaks.

First, the term used in the Anglican tradition for showing mercy to the poor is “almsgiving,” which is usually understood to refer to acts of charity performed in mercy, typically to those who are nearby. It is not just a nice thing to do every once in a while, such as every Lent. Rather, it is viewed as something that God does and also commands us to do. Therefore we participate in His heart of Mercy toward those in need and we incorporate it as a regular spiritual discipline.

Almsgiving is mentioned in the Book of Common Prayer is in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion. For those unfamiliar, these Articles articulate the Church of England’s teaching on various doctrines and practices in the context of the English Reformation. Article XXXVIII says, in part, that “every man ought, of such things as he possesseth, liberally to give alms to the poor, according to his ability.”

Article XXXV references two Books of Homilies that English preachers, many of whom were untrained, could use in their services. They were produced in the sixteenth century and meant to provide a simple yet comprehensive view of the Anglican understanding of the Gospel and the Church. Homily XI in the Second Book of Homilies is on the subject of almsgiving.

“Among the many duties that Almighty God requires of His faithful servants by which He wants them to glorify His Name and declare the certainty of their calling, none is either more acceptable to Him or more profitable for them than works of mercy and pity shown upon the poor who are afflicted with any kind of misery. Nevertheless, such is the slothful sluggishness of our dull nature to that which is good and godly that we are almost in nothing more negligent and less careful than we are in this requirement. It is therefore a very necessary thing that God’s people should awaken their sleepy minds and consider their duty in this matter. It is also appropriate that all true Christians should eagerly seek and learn what God by His Holy Word requires of them; so that, first knowing their duty, of which many by their slackness seem to be very ignorant, they may afterwards diligently endeavor to perform the same. By this knowledge of their duty, godly charitable persons may be encouraged to continue in their merciful deeds of giving alms to the poor, and also such as previously have either neglected or condemned it may, when they hear how much it pertains to them, advisedly consider it, and virtuously apply themselves thereunto.”

For your reflection:

Now read a poem from the Old English Exeter Book. The poems in this book were copied around the year 970, making this the oldest surviving collection of English literature that we have today. The following translation from Old English into modern English is by Jacob Riyeff.

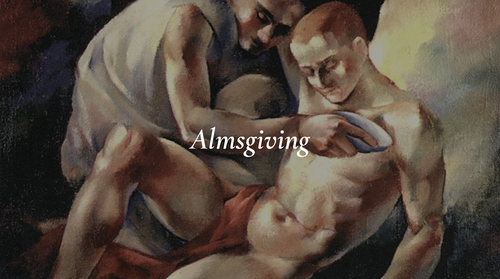

Almsgiving

That disciple is blest whose spirit burns

with generosity, renovating the inner room

of her heart. The world rejoices at her worthiness

and the Lord glories in the welcome glow of her light.

Jesus ben Sirach* says a surging

flame will be snuffed, raging fires

put down with welling water—no longer

able to damage dwellings with burning—

when that disciple douses sin, healing souls

with the gracious gift of her alms.

For your reflection:

First, the term used in the Anglican tradition for showing mercy to the poor is “almsgiving,” which is usually understood to refer to acts of charity performed in mercy, typically to those who are nearby. It is not just a nice thing to do every once in a while, such as every Lent. Rather, it is viewed as something that God does and also commands us to do. Therefore we participate in His heart of Mercy toward those in need and we incorporate it as a regular spiritual discipline.

Almsgiving is mentioned in the Book of Common Prayer is in the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion. For those unfamiliar, these Articles articulate the Church of England’s teaching on various doctrines and practices in the context of the English Reformation. Article XXXVIII says, in part, that “every man ought, of such things as he possesseth, liberally to give alms to the poor, according to his ability.”

Article XXXV references two Books of Homilies that English preachers, many of whom were untrained, could use in their services. They were produced in the sixteenth century and meant to provide a simple yet comprehensive view of the Anglican understanding of the Gospel and the Church. Homily XI in the Second Book of Homilies is on the subject of almsgiving.

“Among the many duties that Almighty God requires of His faithful servants by which He wants them to glorify His Name and declare the certainty of their calling, none is either more acceptable to Him or more profitable for them than works of mercy and pity shown upon the poor who are afflicted with any kind of misery. Nevertheless, such is the slothful sluggishness of our dull nature to that which is good and godly that we are almost in nothing more negligent and less careful than we are in this requirement. It is therefore a very necessary thing that God’s people should awaken their sleepy minds and consider their duty in this matter. It is also appropriate that all true Christians should eagerly seek and learn what God by His Holy Word requires of them; so that, first knowing their duty, of which many by their slackness seem to be very ignorant, they may afterwards diligently endeavor to perform the same. By this knowledge of their duty, godly charitable persons may be encouraged to continue in their merciful deeds of giving alms to the poor, and also such as previously have either neglected or condemned it may, when they hear how much it pertains to them, advisedly consider it, and virtuously apply themselves thereunto.”

For your reflection:

- What struck you from this segment of the homily?

- We do live in a very different world from the time this homily was written. Government aid, technology, travel, etc. may make the reality of living this out a little different. And yet the command of Scripture is the same (e.g., “Love thy neighbor as thyself”; “Whoever is generous to the poor lends to the Lord”; etc.).

- What opportunities and challenges does our society bring to this practice of almsgiving?

- What types of people could be included in our understanding of the “poor”?

- How can the people of God fill in gaps that currently exist?

Now read a poem from the Old English Exeter Book. The poems in this book were copied around the year 970, making this the oldest surviving collection of English literature that we have today. The following translation from Old English into modern English is by Jacob Riyeff.

Almsgiving

That disciple is blest whose spirit burns

with generosity, renovating the inner room

of her heart. The world rejoices at her worthiness

and the Lord glories in the welcome glow of her light.

Jesus ben Sirach* says a surging

flame will be snuffed, raging fires

put down with welling water—no longer

able to damage dwellings with burning—

when that disciple douses sin, healing souls

with the gracious gift of her alms.

For your reflection:

- What does the imagery in this poem suggest about almsgiving?

- In what sense might we see almsgiving as an action that can be for the “healing” of our souls?

Contact a spiritual director

It is common to be confused about Almsgiving? We want to help! If you'd like to contact any of our spiritual directors at Christ the King, simply click the images below.